“Suzani” is one of the most prominent large- scale traditional Central Asian textile arts. In modern-day Central Asia, “suzani” refers to both the large wall-size traditional embroidered tapestry and the embroidery style, used on clothing, home decor and accessories. The ancient art of suzani embroidery continues to play an important role not only in the decoration of the Central Asian home, but also in the life of the people and the pride of traditional folk art. The term “suzani” has recently enjoyed a rise to prominence in the West, but there are several keys to understanding and recognizing authentic suzani.

5 KEYS TO UNDERSTANDING AUTHENTIC SUZANI EMBROIDERY

1. Authentic Suzani is Always Hand-Embroidered

The word “suzani” is derived from the Persian word “suzan,” which translated into English means “needle.” Thus, authentic suzani embroidery is always hand embroidered, though it may be done with a needle and thread or with a tambour hook (similar to a small crochet hook, which is passed through the fabric to create a running chain stitch).

Tambour hook and needles.

The tambour technique is much faster than the needle and thread technique, at least in the hands of an expert. Traditionally, women embroidered suzani with multicolored threads of silk or cotton on large pieces of solid- colored silk or cotton fabric, creating large wall tapestries, bed covers and similar large home décor pieces, as well as elaborate clothing for ceremonial occasions. In more recent times, for both the international and Central Asian markets, the suzani embroidery technique is used on smaller home décor items, such as throw pillows, and clothing for everyday wear. Modern printed or machine- embroidered patterns labeled “suzani” are nothing more than commercial reproductions of the authentic suzani art.

2. Suzani Embroidery Is Steeped in Meaning

The embroidery patterns and colors of traditional suzani are steeped in meaning, and vary from region to region within modern-day Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. (The current political borders of Tajikistan and Uzbekistan were created during the Soviet period, and do not reflect the long-standing reality that Tajik and Uzbek ethnic populations exist throughout both countries and share many cultural traditions, including suzani). Historically, each region and village used different techniques and approaches to the art of suzani and adopted different schools of thought about the craft.

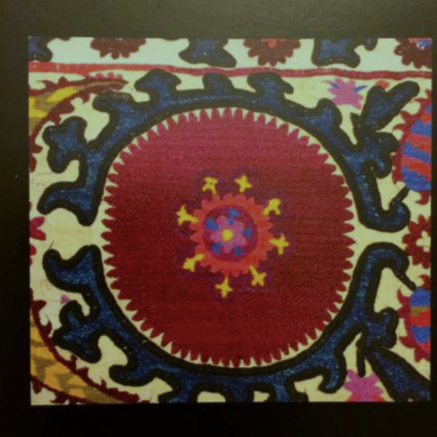

The “rosette,” in the form of a blossoming flower, with its round shape was often perceived as a symbol for the sun and communicated the power of a cosmic force, denoting change, love, beauty, and heavenly life. The sun and moon were typically represented by rosettes, one big and one small, and a whirlpool pattern embodied the cycle of events in the universe.

Numerous "rosettes" appear in this "bolinpush" (bedcover) at the Teahouse "Inturist" in Panjakent.

Panjakent, Tajikistan, which lies just across the border from Samarkand, Uzbekistan, and was one of the key stops along the Great Silk Road between Europe and China, is home to a unique suzani style within Tajikistan, using unusual color combinations and rare embroidery patterns. One common Panjakent color palette consists of pale pink and brown with a sparse composition populated by round elements resembling stars in the sky. This star-like composition iscommonly known as “Sitora.” It has an astrological and occult connotation which can be traced back to the 7th and 8th centuries.

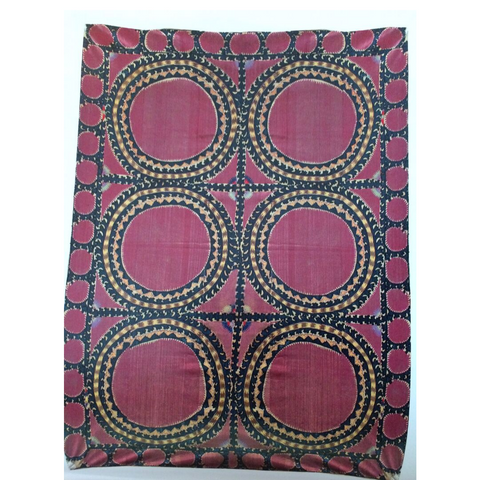

"Sitora" pattern from Panjakent.

In Panjakent, the hand symbolizes the power that protects, creates, and facilitates childbirth. The five fingers represent Muhammed and the four caliphs, the five daily prayers, the five pillars of Islam. This is a theme that presents itself in a Panjakent embroidery pattern known as “Panja."

The 5-fingered "panja" occupies the center of this suzani pattern.

Suzani symbols are arranged to help relieve one’s troubles, such as the use of the evil eye amulet, which is an ancient and popular cross-cultural motif to ward against darkness. In Panjakent, the evil eye amulet is represented as a magnificent five-blossom flower on a long stem, and often decorates a prayer mat, as shown in this photo.

Until more recent times, suzani wall tapestries and other suzani home décor items were always included in a bride’s dowry, both as a symbol of the new bond by marriage and as a spiritual token to protect against evil and endow the young couple with happiness. Often, a girl’s extended family would begin the embroidery work on her dowry shortly after her birth. This suzani dowry practice continues in rural areas and even among many more traditionally-minded families in the cities. Suzani tapestries and other dowry items continue to be passed down through the generations as family heirlooms, though the original meanings are often lost to the latest generations. The modern generation of suzani artisans, like Munira Akilova, have had to rescue the art and its meaning from museum collections and the homes of the grandmothers and great grandmothers of the region.

3. Authentic Suzani Comes from Central Asia

Although suzani patterns have migrated to the West in many forms, authentic suzani embroidery comes from Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and surrounding areas where Uzbek and Tajik minorities have settled and continue their traditions. For example, there has been a significant Tajik minority population in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region of China since ancient times, and there is a large Tajik population in northeastern Afghanistan. The Tajik population is the modern successor to the Bactrian, Soghdian and Persian populations that occupied these areas through the centuries, and many of the intellectual giants of the Islamic Golden Age lived in this to Iranian Farsi, although it is written with a modified Cyrillic script.

4. Traditional Suzani is Left Unfinished

A traditional suzani has a beginning, but there is no end. A part of the embroidery was always left unfinished to be taken up by the next generation. This practice represents inheritance and the continuation of ancestry, as well as a celebration of the expansion of the family by marriage, for which the suzani acts as a gift and meaningful bond.

This unfinished aspect calls to mind the tradition among Navajo rug weavers in the Southwestern US who always include a mistake somewhere in their rug. “The traditional teaching of the Navajo weaving is that you have to put a mistake in there. . . . It must be done because only the creator is perfect. We’re not perfect, so we don’t make a perfect rug.” “Navajo weaver shares story with authentic rugs,” Navajo Times, March 16, 2009

5. Authentic Suzani Typically Features a Combination of Embroidery Techniques and Patterns

The authentic suzani tapestry features a combination of embroidery techniques (usually satin stitch, buttonhole stitch and chain stitch, including couching techniques) and patterns (such as floral patterns, geometric patterns and zoomorphic (animal- based) patterns. These combinations of techniques and patterns embody the many layers of meaning.

For example, in the suzani pattern above designed by Munira, the circle figure signifies the sun, warmth, and the growth in life. The blue five-fingered "panja" in the middle represents humanity in the center of the universe. The rosette flower symbolizes a happy flourishing life. The surrounding white circle in chain stitch symbolizes being surrounded and defended by a pure, successful life. This meaning is emphasized by the use of the color white, which symbolizes purity, clarity, happiness and an easy life. The outer blue circle, which can be viewed as stylized birds' wings, has a dual meaning: freedom and a protective wall. The blue color symbolizes freedom and the purity of water. The yellow color signifies warmth, happiness, and royalty, while the green symbolizes growth and proximity to nature.

Leave a comment